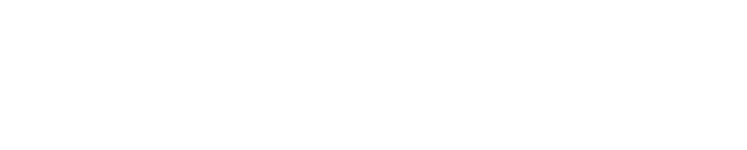

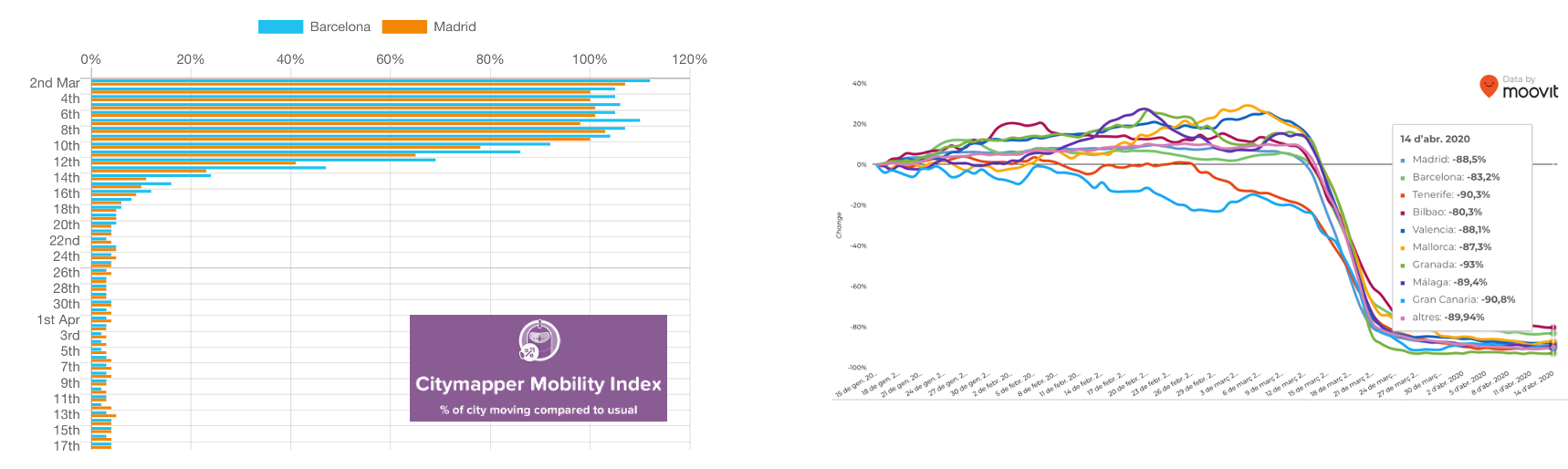

The COVID-19 pandemic has struck an existential blow to Barcelona’s public transport — as well as every other world-city public transport system. Ridership has plunged more than 80% on major public transportation systems in European and US cities since January 15, according to data from Moovit’s Public Transit Index, and cities like Barcelona and Madrid moving 4% compared to usual, looking at revealing data from the Citymapper Mobility Index. For cities in lockdown, this implies public transport is operating primarily for critical workers, many of whom are in the currently endangered and exhausted health sector. This means reduced public transport services and choices that put yet more stress on those critical workers, especially those who do not have access to a personal vehicle.

Barcelona & Madrid % of city moving compared to usual (source: Citymapper Mobility Index) | Impact of COVID-19 on Public Transport usage in Spanish cities (source: Moovit)

The difficult lesson we are learning is that public transport is not only a matter for providing reliable, affordable mobility, reducing petroleum consumption and thus contributing to reduce the overall environmental footprint of transportation, and providing a modest degree of social equity. Significantly, public transport moves a critical body of essential workers to and from jobs that are fundamental to our cities and to each of our lives regardless of social measure. Well-designed, cost-effective public transport is not merely important or good-to-have — it is existential.

Because not every critical worker has personal or public access to transportation at every time and place needed, the commercial, for-hire-vehicle industry — taxi or ride-hailing — is also existential for all of us and for our cities.

Worse than the immediate and crushing set-back for these two transportation sectors — public transport and commercial ride services — is that the economic and structural recovery time for each will be significant, likely several times longer than the pandemic’s direct health impact, itself an unknown. Worse still, if left to their prior devices, public transport and commercial ride services will return to their non-cooperative behaviours, slowing each other’s recovery.

There are many factors involved in the less-than-optimal configurations of public, commercial, and personal mobility fleets. One of these is the competition between public and commercial fleets in terms of accessibility, convenience, price, and service redundancy. There are times and places that each one clearly out-performs the other: public transport at rush hour, ride-hailing or taxi late at night.

The core market failure, here, is that public transport, taxi and other shared mobility services are simultaneously in oversupply downtown and in undersupply in the suburbs. They compete where the money is instead of collaborating to satisfy the full demand horizon.

To be fair, public transport is not strictly “business-oriented” in the sense of seeking to serve only profitable areas, but obviously its deployment is focused where there is more demand, thus leaving many edge users underserved. This means more private cars in suburbs than might otherwise be needed, and once purchased those vehicles often find their way downtown.

The weak, usually incidental, collaboration between public and commercial fleets in most cities ensures a massive missed opportunity to optimize urban mobility while reducing private car ownership.

However, there is a way to govern collaboration between public transport and the for-hire-vehicle industry to ensure critical and affordable transportation services in circumstances where public transport is unavailable and taxi usage is otherwise prohibitively expensive for many users.

Taxi line at train station (credit: Victoria Pickering on Flick)

For example, rather than subsidizing a bus to run every 30 minutes on a route with only five or six customers, a better option would subsidize a local taxi or ride-hail to take health-care worker Jaume to the train station 4 km away so he can get to the hospital where he works. Or, instead of funding a late-night bus, with unsustainably few riders, subsidize taxi use after a certain hour and within a specified zone to bring Celina home after her late shift as a security guard.

Our proposal: a social-geography method of micro-subsidies that are targeted at trips rather than vehicle fleets

We propose a cloud-based platform, available automatically to mobility apps, and operating without disclosing a user’s personal information. This would be based on planner-defined geographic tracts (catchments) and municipally-approved micro-subsidy schedules designed to fill public transport gaps — i.e., especially where and when there are underserved users. These micro-subsidies are available in places and at times where public transport is not, but are absent when and where public transport is available. Subsidies can be shaped to encourage ride sharing, alternative-energy vehicles, and incorporation of public transport for part of a trip. And subsidies can be dynamic and can be set to be just enough to make the use of public transport preferable to the use of a private car.

This harmonizing system draws individual subsidies from pre-assigned pools which are managed to maximize passenger trips rather than bus-kilometres. For example, it knows to only subsidize a trip that originates in a particular underserved area (a catchment that may have several thousand homes), such that the trip terminated at the closest train or bus station. Or vice versa.

Because of its use of subsidized catchments, this platform service provides anonymous maps of the densities and times of passenger movement for planning purposes. These cannot be reverse-engineered to determine personal passenger information.

This harmonizing approach is designed to balance the availability of transportation in cities using public and commercial services and without relying on private vehicles. This will be of critical value in times of transportation stress such as in the post COVID decades.

This platform consists of three critical components:

- A subsidy pool is defined by a Public Transport Authority or City Council to be used to address specified gaps such as underserved times and places. For example, a subsidy of, say, €100,000 might be assigned to bring riders in a specifically named and mapped suburb to the north of a city (catchment area) to one of the train stations at its perimeter. The public transport authority would identify that subsidies of, say, €2.40 may be applied to any for-hire conveyance (including bike-share) that originates in the defined catchment area. In the case of an extensive catchment representing some longer trips the catchment can be subdivided and a larger subsidy provided for farther distances as needed. Easier yet, a micro-subsidy can be calculated as a few cents per kilometre.

- A MaaS app that permits a user to request a trip and have the available subsidy for that trip included in its pricing calculation. The user of that app needs to know nothing except that taking a ride to a public transport hub is now better than using a personal car. Additionally, social distancing can be factored into the overall concept and UX, so that a user can make sure that all legs of his/her trip ensure safe distance with other travellers (also, users can report on actual conditions, such as level of occupancy), and include additional, relevant information such as the availability of hand sanitizers in for-hire vehicles, disposable gloves for micromobility services, or whether vehicle touch-surfaces are coated in self-cleaning materials to reduce the viability of bacteria and viruses.

- A regional server that holds all the maps for all participating catchment areas within the region, all the related subsidy pool accounts, all the schedules, and all the rules used to calculate and apply subsidies in real-time. In other words, this third component is a specialized GIS system — a sophisticated geographic calculator.

In summary, the harmonizing platform we’re proposing is purpose-designed to balance the hundreds of local cost and access equations of transportation in our cities without reliance on private vehicles. It grows public transport ridership and for-hire vehicle use at the expense of private vehicle ownership. Its flexibility and resilience would be of critical value in times of stress such as now. Overall, it aims at tuning these two segments of the mobility industry while growing active modes and shrinking private motor-vehicle ownership.

Nudging users into public transport with flexible, affordable (micro-subsidized) mobility services

Users deserve nimble deployment of fruitful innovations to ease their lives. Our cites deserve the same to preserve them as places of growth, health, and livability.

According to a survey by the University of Sydney Business School, about half of all people living in major Australian cities would abandon their private cars if they could travel up to five kilometres to a public transport hub by Uber or taxi for a capped fare of $5. Ride-hailing partnerships are being developed in dozens of communities across North America, all attesting to the fact that companies like Uber and Lyft can supplement or substitute for traditional service in some fashion. In certain cases, ride-hailing is replacing under-used bus routes. In others, it’s responding to 911 calls, paratransit needs, and commuters traveling the last leg of a transit trip.

We at Factual are eager to explore further interest in our proposed concept to be implemented in European cities, a substantially disruptive approach to boosting public transport and addressing some of its inefficiencies while alleviating the mobility inequalities facing citizens living in suburban areas with poor-to-no public transport on offer. Whereas influential actors, such as the UITP, have offered thought leadership on how to combine new mobility and public transport mainly focusing on the urban space, where there is more “competition”, the challenge we are proposing to address includes vast tracts of underserved suburban catchments that pour private vehicles into rail-hub parking lots or directly into the city centre.

However, UITP’s Policy Brief “New Mobility and Urban Space: How Can Cities Adapt?” does introduce the concept of “Mobility Hubs”, a “physical MaaS” or “dedicated urban space where all transport options are available, from public transport to bike facilities and shared modes, and including delivery services” which “can be implemented near major transport hubs or in smaller cities and lower density areas”. Our harmonization concept is being developed to offer last mile solutions and provide additional flexible transport options currently out of reach for many public transport users, e.g. connecting them to such “Mobility Hubs”.

In tough times when Public Transport Operators are faced with plummeting usage, more than ever we must think beyond our usual box and bring in critical new solutions to avoid going back to a “new normal” where personal car usage increases (as we’re already seeing in some Chinese cities after lifting the COVID-19 quarantine)

To learn more, and discuss opportunities to develop Proof-of-Concept or pilots based on our harmonizing platform do not hesitate to contact Factual at info@factual-consulting.com or leave us a comment.

#flattenthecurb #flatteneverycurve #covid19 #coronavirus #newmobility #MaaS

Co-authored by:

Josep Laborda (Co-Founder and CEO at Factual)

Bern Grush (Strategic Advisor to Factual, Chief Innovation Officer at Harmonize Mobility Inc.)