by Maria Kopp and Carola Vega. Originally posted in Spanish on paisaje transversal blog.

Rural areas in the European Union play an essential role on the continent. They’re home to 137 million people, approximately 30% of the population, and cover over 80% of the territory. These regions serve as natural havens and productive spaces with high development potential. One aspect that is underdeveloped is rural mobility; that’s what we’re going to focus on in this article.

However, the social and economic landscape has undergone significant changes. Globalisation and urbanisation have directly impacted the role and nature of rural areas. They face unique challenges such as low population density, geographic and institutional isolation, predominantly agricultural economies, and low incomes. These challenges have a tangible impact. Projections indicate that in the next three decades, eight million people will leave rural areas of the EU in search of opportunities in urban areas.

This migration trend is prevalent among young people seeking employment opportunities. It leaves behind vulnerable demographic groups such as the elderly and those with low incomes. A gender imbalance is also evident in this trend. More women than men leave rural regions due to even more limited employment prospects. This contributes to what is termed “rural masculinisation.”

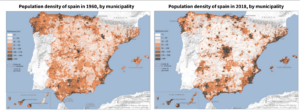

Own illustration

These trends are not entirely new. Urban migration has been ongoing since the second half of the 20th century; rural exodus has become tangible across Europe. It affects North, South, and East regions, including countries like Finland, Sweden, Spain, and Portugal, and areas in eastern Germany. In Spain, for instance, rural areas have experienced a 28% decline in population over the last 50 years. This contributes to the phenomenon known as ’empty Spain’. However, rural areas in Spain still house approximately 16% of the country’s total population and cover 84% of its surface area, underscoring their importance in national development.

INE, Population Census 1960 and Census of Inhabitants 2018

In 1998, the European Commission expressed concerns about the future of rural areas in the report “The Future of Rural Society.” In 2016, an OECD report reaffirmed the impact of living away from cities on economic growth, living standards, and overall well-being. Similarly, the 2021 World Social Report from the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs highlighted the importance of rural development in achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), leading to a long-term vision for rural areas in the European Union.

Rural Mobility and Development: an Endless Cycle

Mobility has long been a critical factor in driving rural development. However, low-density areas and urban centres show a significant mobility gap. While cities are implementing a wide range of transportation options to cater to diverse user groups, adapting these solutions to rural areas presents challenges. For example, micromobility solutions such as electric scooters are not suitable for covering long distances in low-density areas, limiting their impact and usage. On the other hand, conventional transportation systems like bus lines struggle to be financially sustainable in rural environments. The low number of passengers hinders efficient scheduling, and the resulting low revenue poses challenges for system maintenance and improvement, leading to operational and structural difficulties. Consequently, many rural areas have become what is commonly referred to as “transport deserts,” where inadequate public transportation services restrict options and opportunities for local communities.

In addition to the mobility gap, there is a digital divide in low-density areas. The exodus of young people to promising cities has resulted in an ageing population relatively older than the national average. Emerging concepts of digital mobility, thriving predominantly in urban environments, such as car-sharing and mobility as a Service (MaaS) options, cannot reach their full potential in rural areas.

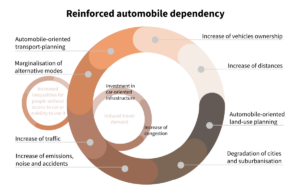

The evident mobility gap and digital divide perpetuate the persistent dependence on cars in rural regions. However, many people living in rural areas cannot drive or do not own cars, especially those belonging to vulnerable population sectors. Consequently, mobility in rural areas often becomes a self-perpetuating cycle where low accessibility generates higher demand for mobility, turning mobility into a source of new inequalities that feed the vicious circle of rural mobility.

Own illustration based on Transformative Urban Mobility Initiative, n.d.

Moving Towards New Approaches in Rural Mobility

Overcoming the challenges of mobility and digital connectivity in low-density rural areas requires innovative solutions tailored to their specificities, moving away from traditional urban approaches. While eliminating cars from areas where they are essential is unlikely, the primary goal is to reduce their dependence.

30-Minute Rural Communities

Integrated planning focusing on reducing travel becomes essential to forging accessible communities in low-density population regions structured around transport nodes. Often overlooked, this strategy clashes with the current practice of allocating land for single-family homes and commercial areas disconnected from public transportation. While cities embrace the idea of the “15-minute city,” concepts like the “30-minute rural community” prioritise accessibility to essential services within a sustainable half-hour travel radius.

Redefining Connectivity in a Multimodal Environment

In Flanders, the Flemish government’s Department of Mobility and Public Works has opted for a strategic policy instead of isolated transport solutions. They offer various modes of public transportation, such as buses, taxis, minibuses, and shared cars, tailored to the needs of each area. The highlight is the seamless connection guaranteed by “Hopping points,” points that facilitate the transition between modes of transportation and enhance the overall travel experience.

Flexibility in Conventional Bus Systems

The flexibility of conventional bus systems has the potential to reduce dependence on cars, making personal vehicles a choice, not a necessity. Demand-responsive transport (DRT) systems analyse passengers’ needs in real-time, optimising routes and merging the flexibility of taxis with the structure of fixed public transportation. In Spain, Nemi is a prominent example, offering DRT software solutions. Launched in 2018 in the Metropolitan Region of Barcelona, Nemi has expanded to Catalonia, Greece, Portugal, and the United Kingdom, with 40 active services. In 2022, over 6,382 passengers in Garrotxa, Catalonia, benefited from Nemi’s DRT, with over 80% of users using the mobile app for bookings.

Bottom-Up Mobility Initiatives

Community efforts and volunteering can provide alternatives in regions where municipal budgets struggle to maintain bus routes. In Germany, around 350 “Bürgerbusse” or citizen buses, operated by volunteers organised in registered associations, allow door-to-door trips and connection to the public transportation network. In the Mecklenburg Elde-Quellgebiets region, the ELLI bus service provides around 150 monthly trips.

Sharing is Caring: Shared Travel Models

Carpooling can benefit rural and suburban regions by connecting passengers with private drivers making similar trips. This approach resembles formalised hitchhiking, allowing passengers to specify pick-up and drop-off points. Karos’s carpooling service in France facilitated nearly 3.8 million shared trips between 2017 and 2021 in 760 suburban and rural municipalities, covering 91% of the regional population.

Effective Simplicity: Merging Furniture and Transportation Services

The concept of “Mitfahrbänkle” (Car-sharing Bench in German) is simple and elegant: strategically placed benches in public locations serve as meeting points for car-sharing, indicating different destinations. This novel combination of a car-sharing app and public furniture has gained popularity throughout Germany since 2010. For example, in Schuttertal, a German town with around 3,200 inhabitants, more than 13 “Mitfahrbänkle” have been installed, with approximately 400 registered drivers proudly displaying official accreditation stickers on their vehicles.

Connecting People and Goods

Public transportation has been designed to offer affordable mobility in specific areas. Often, existing passenger routes connect remote regions with urban centres, benefiting areas with scattered populations and limited logistical demand. By using these routes for package delivery, economic solutions are generated. Users can easily book package deliveries at designated bus stops, specifying the time and destination. Since 2012, the KombiBus project in Brandenburg, Germany, has successfully demonstrated this concept, boosting local employment and production through increased market access. The TEISA transport operator in Spain adopts a similar model in the Pyrenees.

In summary, addressing rural mobility challenges goes beyond innovation. Rural areas play a fundamental role in national and global development and should be included in pursuing a sustainable future. To bridge this gap and promote rural development, it is essential to recognise that rural areas are not uniform and present unique challenges. This diversity demands a combination of solutions tailored to the needs of each rural community. Adopting a citizen-centred approach, actively engaging citizens, and exploring a wide range of mobility solutions are imperative. Within these ecosystems, challenges present opportunities for new ideas and innovative combinations.

Diversifying solutions is vital. Integrating and prioritising public transportation with personalised and shared mobility services, including collaborative and volunteer-based options, can significantly address rural mobility deficits. Better regulation and governance enable these connections and are often crucial to public-private partnerships, intersectoral coordination, and, of course, the indispensable involvement of local actors. Effective governance with assigned responsibilities is crucial, especially since most European countries lack comprehensive rural mobility policies.

Maria Kopp is a Consultant at Factual Consulting, holding a degree in urban and rural planning, and her work focuses on the relationship between social inclusion and justice in mobility.

Carola Vega is an architect and urban planner with experience in strategic planning. She is currently a Senior Consultant at Factual, leading European innovation projects in mobility and collaborating with various cities to develop and pilot sustainable mobility solutions.