Author: Josep Laborda (Factual)

In most European cities, the networks of roads, parking and fuelling infrastructures have been historically designed to promote and respond to the needs of cars and trucks at massive scale. Indeed, the dominant transport mode today is still fossil-fuel, privately-owned vehicles, which are widely regarded as being inefficient – causing congestion, stress, waste of time, accidents -, polluting, and noisy – causing public health issues, and make an uneven use of public space.

In figures, EU transport represents almost 25% of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, road transport being by far the biggest emitter accounting for more than 70% of all GHG emissions from transport, and thus the fastest-growing contributor to climate change, according to the International Energy Agency. It is also responsible for a large proportion of urban air pollution: an estimated 3.5 million premature deaths were attributed to ambient (outdoor) air pollution in 2017, with road transport estimated to be responsible for up to 30% of particulate emissions (PM) in European cities, mostly due to diesel traffic. It all has a huge economic impact: indeed, the European Commission (EC) estimates health care costs due to air pollution to be between €330 to €940 billion per year, with traffic as the largest contributor. Traffic congestion is often located in and around urban areas and costs nearly €100 billion, or 1% of the EU’s GDP, annually, according to the EC.

Avoiding the most negative effects of climate change requires reimagining and reinventing our great urban areas to put them on a path toward a zero-carbon future. Innovation in urban mobility holds great potential to foster this impending transformation, as the impact that can be unlocked is huge. Now, I wonder…

Is Mobility as a Service a silver bullet for the impending challenges facing transportation? The answer loud and clear is: MAYBE (provided the right strategy is put in place, and there is vision)

MaaS can certainly be an effective tool to pursue ambitious environmental goals by nudging users away from private cars while fostering a more carbon-efficient mobility mix, facilitating access to public transport, promoting active mobility – walking and cycling – and zero-emission shared mobility. In order to pursue this mission, MaaS must be steered towards promoting a fundamental paradigm shift, where public and private stakeholders do not “compete” for the same users (or customers), but come together to exploit their genuine strengths (and acknowledge their respective limitations), and jointly develop strategies to gain market share to the still dominant mode, i.e. the privately owned car, fostering market dominance of clean technologies and fuels. That said, private vehicles cannot be simply banned from cities and blamed as the sole source of all negative externalities caused by ill-conceived transportation systems, as some user segments might not have competitive alternative mobility options (for example commuters having not convenient access to public transport), and so we must think of intermediate approaches where users have real alternatives to driving.

The urban mobility challenge is multisided and demands unbiased, open-minded, inclusive approaches, definitely not the vague, too often void promise of “freedom of mobility”, which intentionally overlooks the inherent complexities of mobility hidden (or not that hidden) behind marketing statements, and is certainly not inclusive, and not necessarily aimed at meeting sustainability goals (but profitability from a business model perspective). Fair enough, MaaS is increasingly a viable option for an growing number of early adopter city dwellers (though inclusiveness remains an issue for some user segments, such as the elderly or non-digital native), but in order to leverage MaaS expected benefits at large (both for society, climate, and for companies striving to be profitable in this very competitive market), MaaS has a largely unmet opportunity to also cover interurban and rural areas (where the offer of mobility services is much less abundant and ubiquitous than in cities, and where a huge proportion of mobility inefficiencies in cities originate). In order to do so, more innovative approaches (beyond the plain concept of MaaS) must be put in place, because MaaS is a concept that can also “work” in such environments, provided the right incentives are available for users not to commute in their private vehicles, while they come to love the convenience of avoiding the hassle of driving (and parking), make the most of their commuting time, save money, and contribute to mitigate climate change one trip at a time.

Public authorities must prove to have strategic capacity to transform and develop stable operational frameworks for cleaner mobility, including innovative approaches to cross-sectoral planning, public participation and procurement, and the shared use of embedded physical and technical infrastructure, and so ultimately contribute to reduce congestion, emissions and pollution, while work towards meeting the ambitious “Paris Agreement” 2030 targets, furthermore supporting the recent “European Green Deal” long-term strategic vision for Europe to become the first climate-neutral continent by 2050, as well as the EU mission areas on climate-neutral and smart cities that will drive the next Horizon Europe programme.

MaaS alone cannot significantly contribute to meet the above-mentioned sustainability goals if implemented in an isolated, non-systemic manner, and will definitely not deliver on its promise without a sound, resilient, and flexible governance scheme revolving around two essential pillars (which can be broken down into a number of interventions):

- First, an effective Public-Private Partnership aimed at meeting societal goals (in terms of sustainability, efficiency, inclusion, equity) while ensuring a level playing field for private on-demand mobility services to be able to develop viable business models, avoiding conflict with incumbents, ensuring an even use and share of public space, which must be redesigned with a citizen-centric approach for more liveable urban spaces, and a harmonised transportation system where public transport remains the backbone of mobility.

- Second, unlocked access to (still massively siloed) mobility-related data turned into KPIs (and methods how to obtain these) to measure actual accomplishment of environmental goals, to understand how specific measures under a global MaaS strategy perform, and consequently enable brave, informed decisions to tackle climate change for real. Mobility data management at scale obviously requires meeting stringent requirements as regards security and privacy, and providing workable conditions for mobility service providers to open access to their operational data while protecting their legitimate competitive concerns.

Once (ideally) a suitable governance framework is in place that works for a given city, metropolitan area or region, actual implementation becomes critical, where there is obviously not a unique recipe for MaaS deployment that is capable to get real traction, raise user acceptance, and nudge behavioural change towards more climate-friendly mobility choices, while meeting public and private goals all at once. Much has been proposed as specific measures to enable MaaS.

We at FACTUAL advocate the following (surely atypical) disruptive, forward-looking measures to boost MaaS as we move towards the “next normal” after COVID19, and to counteract some negative early effects after lockdowns, such as a significantly increased use of private cars (and back to polluted air in cities) due to the fear of not being able to keep social distance:

- “Flatten the demand curve”: implement measures to avoid peak hour commute, promote a fundamental cultural change from public authorities and companies alike towards favouring more flexible work schedules, and so safer commutes (ensure social distancing), and thus reduce congestion, and pollution. We propose analysing in depth the mobility patterns and mechanisms how people (and freight) are moved so to recover economic activity while adhering to new safety standards.

- Facilitate that more users conveniently are conveniently connected to public transport by implementing micro-subsidy schemes and economic incentives to first and last mile privately-operated mobility services (where otherwise eligible users would keep commuting using their own private, polluting, much less efficient vehicles); micro-subsidies can be implemented both by public authorities, and private companies willing to develop a safer, healthier mobility culture for employees as part of their Corporate Social Responsibility, or retailers willing to attract more customers to brick and mortar businesses through the implementation of loyalty schemes where sustainable transportation services are incentivised. Our definition of micro-subsidy is a very small (usually single-digit) subsidy targeted for a particular time, and place, and purpose. Examples are 2€ for a 4€ bikeshare to the train station, or 9€ for a pensioner to take a 17€ taxi to the hospital.

Our proposed innovation is a SaaS platform, micro-subsidy calculation engine comprising a database with geographic information on eligible areas and a set of rules that can be adjusted in real-time to ensure micro-subsidies fill gaps in public transport and support wider policy objectives, and it can be easily plugged into any MaaS platform, capturing more users into public transport. It takes a small investment in public transport subsidies that are surgically targeted at specific gaps and turns that into additional ridership, and reduced vehicle km travelled. The increased public transport ridership pays back the investment, and reduced vehicle km travelled contribute to the global effort to mitigate negative externalities caused by the private automobile (accidents, congestion, air pollution). Our concept is simple enough to have been demonstrated with good acceptance in several “walled garden” implementations in North America, and we ambition to take it successfully to an open European market, and then to scale globally.

Read more on the MVP component that FACTUAL has developed aimed at upgrading existing MaaS platforms to implement micro-subsidy programs:

A brave new way to a more resilient public transport after the pandemic

While the world is temporarily closed, how can we rethink public transportation and shared mobility?

There is an exciting, controversial debate these days on the idea whether or not to finance micromobility (or other privately-operated mobility services) with public money. A few excerpts from a recent article by David Zipper are aligned with our vision, such as having found that in some American cities “30 to 55 percent of e-scooter trips would have otherwise been taken by automobile”, asserting that “dockless e-scooters can provide a first-last mile solution for public transportation, enabling riders to reach a transit stop that lies beyond the typical quarter-mile walking radius” or that “docked bikeshare can replace car trips and also serve as a first-mile, last-mile connector for transit”.

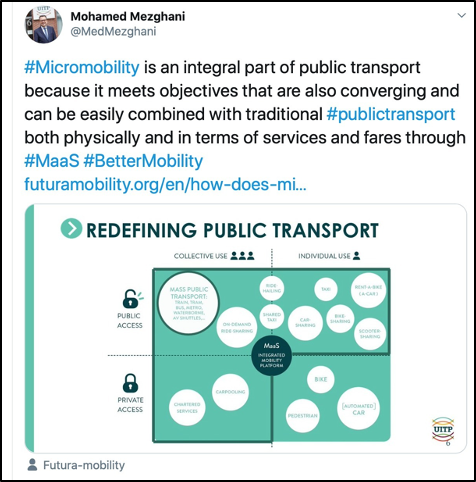

Moreover, and well-aligned with our proposal, Mohamed Mezghani, UITP Secretary General has recently tweeted that “Micromobility is an integral part of public transport because it meets objectives that are also converging and can be easily combined with traditional public transport both physically and in terms of services and fares through MaaS”

On the sustainability endeavour for MaaS, it is important that end users become aware of their CO2 emissions and their impacts, then get familiarised with what MaaS offers in their area, while public authorities must stimulate (or enforce) mobility services to be provided through fleets of shared zero-emissions vehicles, and establish compelling incentives schemes to nudge massive change in travel behaviour and choices towards clean mobility. It must be a “win for all” approach, where it pays off to deploy clean mobility services (from the transport service provider perspective, i.e. business-wise), to purchase clean mobility packages through MaaS providers and so abandon privately owned cars (from the user perspective), and ultimately contribute to meet ambitious environmental goals benefiting society as a whole (from the city perspective). We’re proposing that private mobility service providers cooperate with public authorities to find win-win scenarios with public transport, especially where there is an unmet demand, and a clear complementarity.

The few existing MaaS schemes have proved to be popular with their users. The scale of deployment and uptake remains still relatively small, however. For this reason, climate-aided MaaS will not achieve its potential impact unless it can capture the mobility needs of an entire community, and for the majority of their travel and transport needs

Most MaaS schemes claim a positive potential impact on the environment, but very few treat CO2 reduction as one of their top priorities for investment. A study conducted by the International Transport Forum in Helsinki (2017) found that replacing all private car trips in the city with shared rides would reduce 34% of CO2 emissions from cars, and congestion would be reduced by 37%. So the promise is recognised, but there is yet very little evidence of such impacts (besides that assuming users are prepared to massively opt out of cars is still a too bold statement).

In order to advance MaaS schemes aimed at addressing climate issues we need more:

- User research to understand user acceptance levers (including gamification, raising awareness on one’s carbon footprint) to foster cleaner mobility choices; citizen engagement and co-creation, and testing of innovative solutions under living lab environments.

- Assessment of micro-subsidies strategies, including analysis of the economic viability (business models) of different climate-friendly MaaS schemes, as well as development of forecast scenarios based on expected buy-in.

- Development of governance guidelines and best practice by public authorities ensuring an open MaaS marketplace that is aligned with an overall goal to reduce emissions.

Wrapping-up, in order for MaaS to be an effective tool for urban areas to address climate change and achieve a more resilient transportation system what is needed is less void rhetoric (something many MaaS propositions suffer from), and an effective governance scheme with a strategic focus, with more measurable evidence how concrete MaaS implementations generate true, lasting impact.

FACTUAL is a boutique innovation and strategy consultancy focused on mobility. Reach out to us if you want to learn what we’re cooking!