Author: Josep Laborda (Factual)

Getting around the city using new mobility services is becoming commonplace. In just a few taps on an app users can today get access to a wealth of ready-to-use vehicles just around the corner.

Conveniently. Swiftly. Fun.

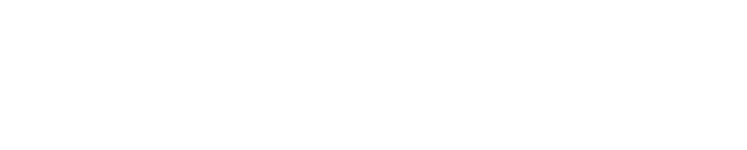

As users locate, book, pay for, and ride a shared vehicle they produce loads of data. And so they do when they use public transport. Indeed, public transport authorities, operators, and cities worldwide have become open data pioneers by widely adopting data standards (such as the ubiquitous, de facto standards GTFS and GBFS) and leveraging them to implement data-driven mobility strategies. Unfortunately though, mobility data is still too often kept in silos, hindering its potential for gleaning deeper, actionable insights. New (and not so new) private mobility operators are generally more reluctant to open their data, if not forced to, or if the right incentives are not available (such as mutually beneficial Public-Private Partnership models towards the realisation of MaaS). For cities, access to data from mobility operators providing their services in the public right of way is a priceless tool for enabling more informed mobility planning and management. For mobility operators it can provide valuable information to enhance their competitiveness and improve the efficiency of their operations.

Several hurdles must be overcome for mobility data to unlock its (huge) expected value: the lack of trust between the different players in the highly competitive urban mobility market, the need for standards enabling interoperability, and a level playing field setting the legal, regulatory, and technical conditions for effective, secure, and fair data sharing (and monetization)

Data as a game-changer for urban mobility

As new mobility services continue to evolve and change the urban mobility landscape, it is critical, and strategic, to leverage new mobility data to evaluate and understand how these are reshaping our communities on everything from equity, inclusiveness, road safety, and the environment (aka sustainable mobility).

Because cities did not act quickly enough to set data sharing frameworks when ride-hailing companies burst into the mobility market a decade ago, and with new shared mobility services still in their beginnings (or in their infancy, if we refer to micromobility), cities now have the not-to-be-missed opportunity to avoid repeating the same mistakes and so require the data they need that will better inform their decision-making as regards mobility planning and management.

To do so, cities will need to set clear, indisputable data sharing requirements to mobility operators that identify what information they are seeking to acquire, how it will be collected, processed, shared, and stored, the quality, accuracy, format (that is, standards), and frequency of the requested data, as well as determine clear privacy guidelines to protect both the end users, but also the legitimate concerns from mobility operators on commercially sensitive data. It is worth underlining the fact that the definition of personally identifiable information (PII) is rapidly changing and varies considerably from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, so it will be important for cities to be clear about what they are to consider PII and how best to manage and protect those data, where GDPR has laid out a specific set of regulations that deal with PII.

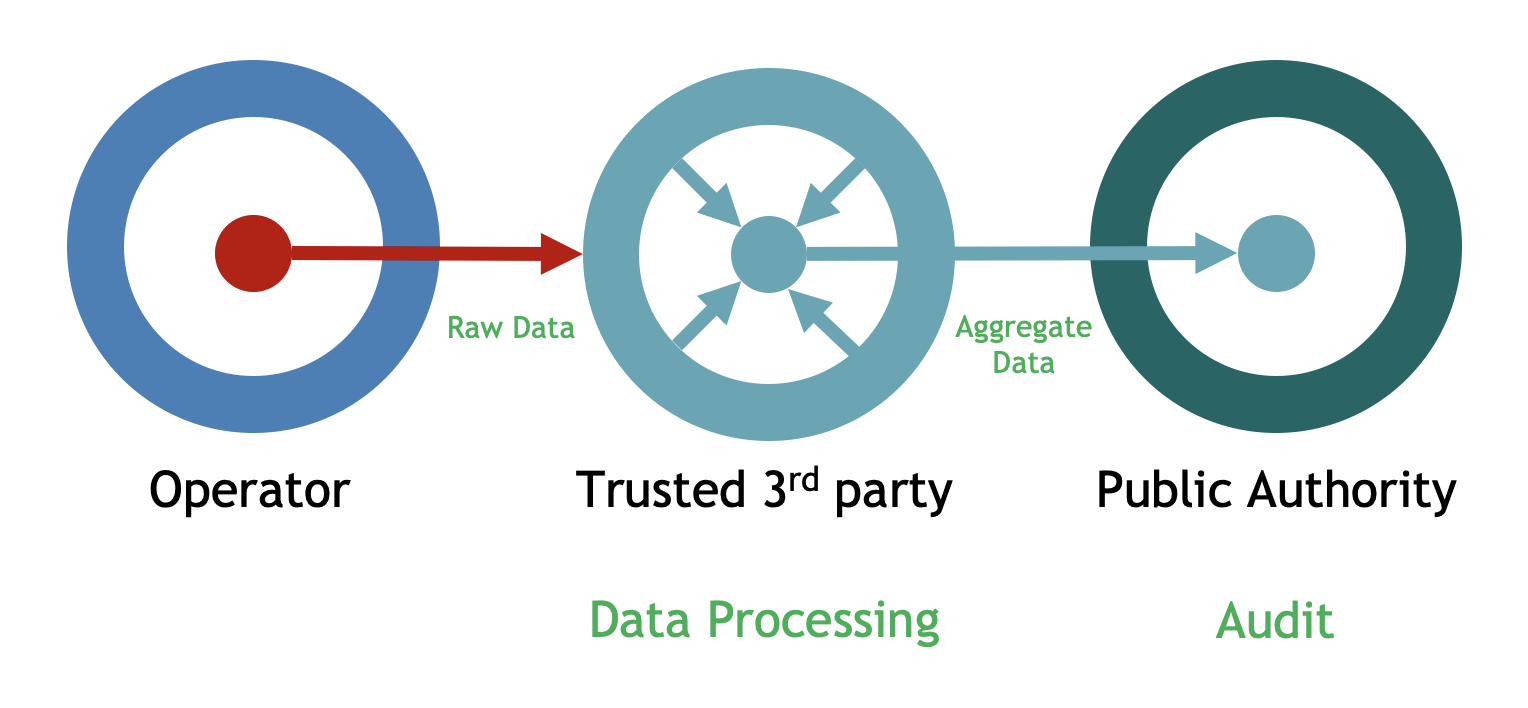

Figure 1 A 4-step framework for effective mobility data sharing (source: UC Davis+ own elaboration)

Trust architecture models for mobility data sharing

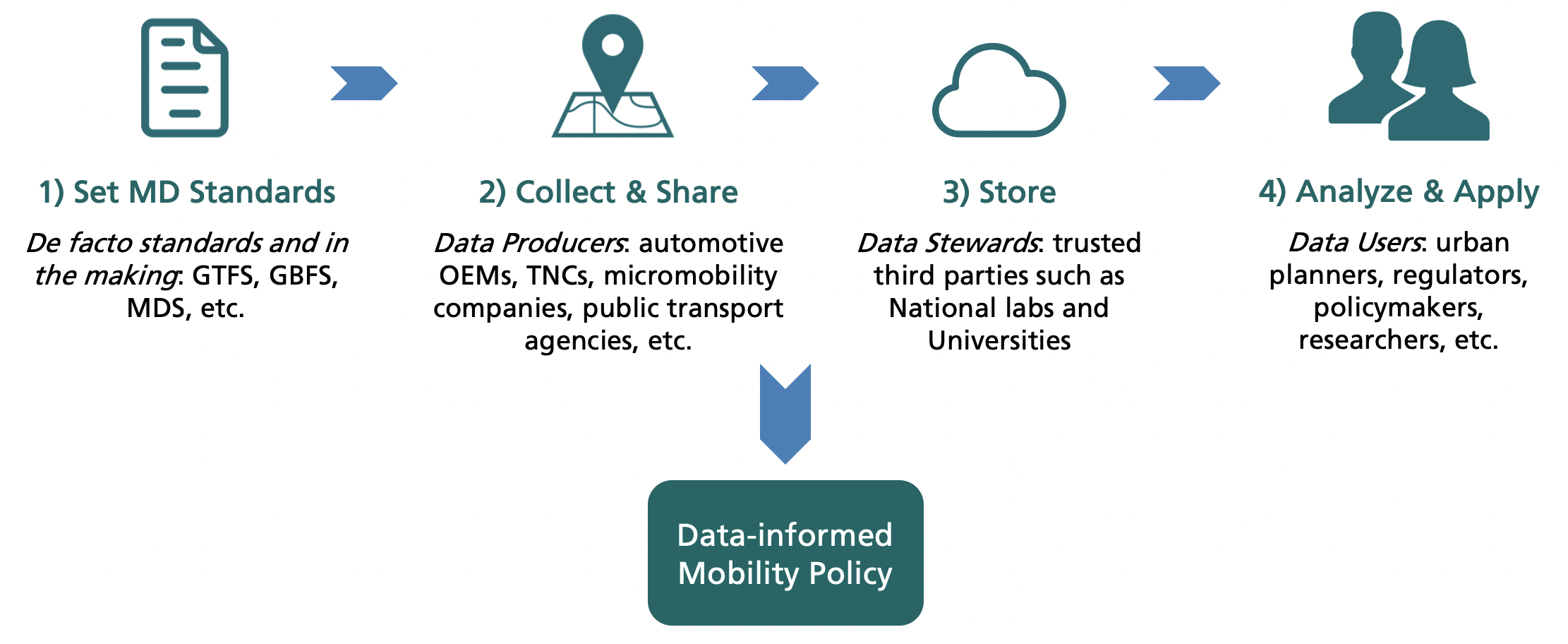

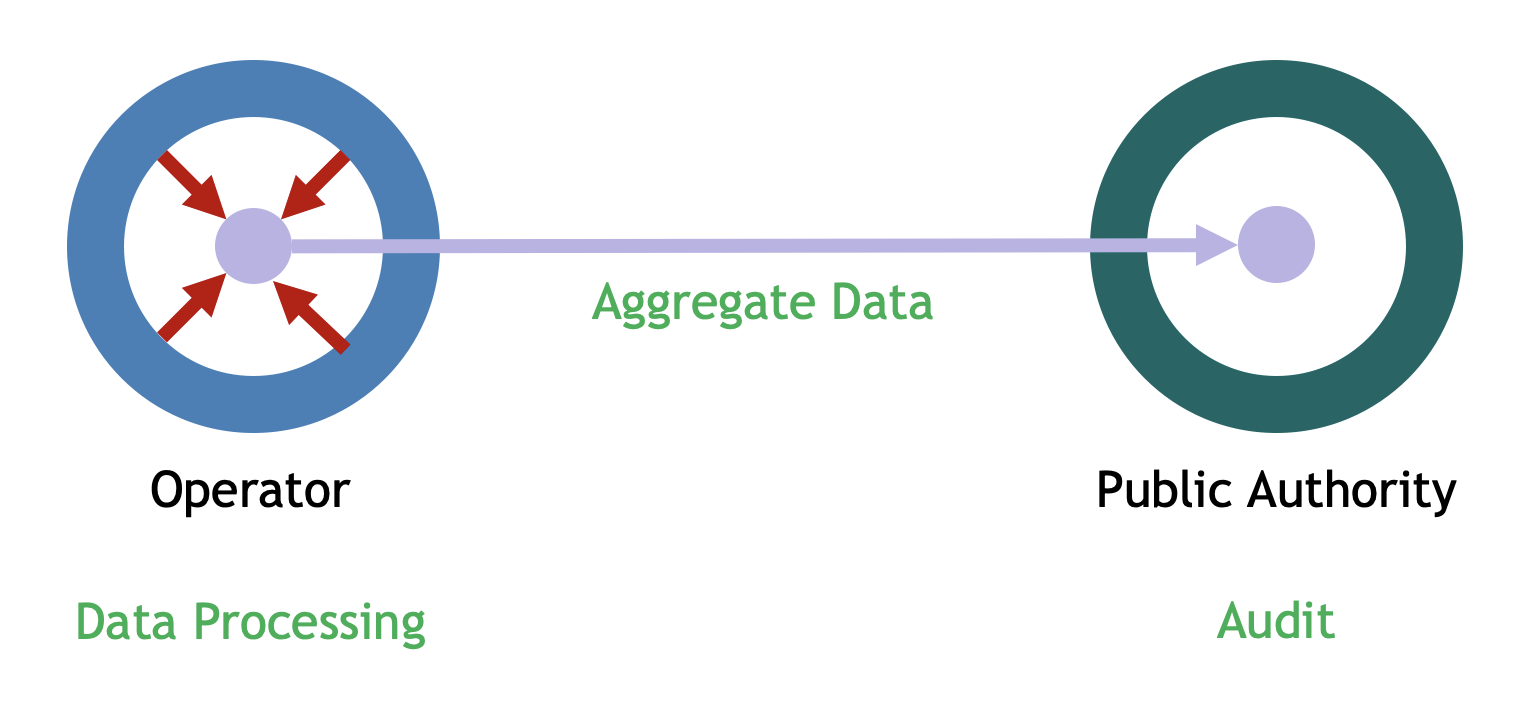

As usual in mobility one size does not fit all. Any framework for mobility data sharing implies that mobility operators and public authorities must cooperate and establish some level of trust with each other, where trust is linked to transparency on purpose, use and data minimisation principles. We basically differentiate three schemes, where it is ultimately up to cities to define which model suits them best.

Mobility operators can provide the requested data to the city’s governing agency directly, and this can be done basically in two radically different ways, carrying different implications:

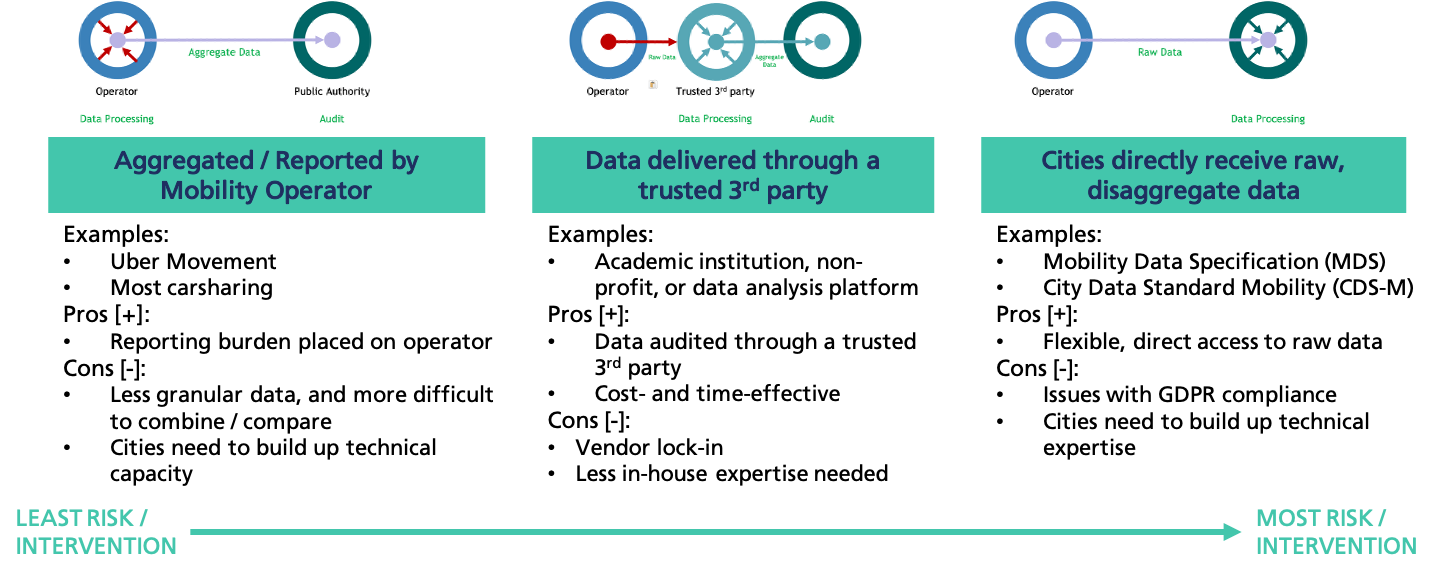

- When operators do not trust public authorities or are reluctant to share their data because they feel their users’ privacy, or their competitive advantage might be compromised, they “cook” data first by aggregating them, and only then they provide a subset of data to public authorities, which might use them for auditing purposes. This is the case, for example of Uber Movement, where the company releases datasets to the public in support of urban and transportation planning. To prevent user privacy issues, Uber aggregates car GPS traces into small areas and releases free data products that indicate the average travel times of Uber cars between them. Although this is certainly somewhat useful, some might as well consider it rather a PR strategy, where some researchers have even pointed out the extent to which such data is actually helpful at all to support or inform any mobility strategy. Overall, it is quite evident that Uber and other mobility operators are generally rather reluctant to share raw data with public authorities, which is the next scheme we analyse, where…

- … Cities do not trust operators, and so they mandate that operators send all the raw data they generate while operating their services. A remarkable initiative designed to govern data sharing from shared micromobility service providers to cities is the Mobility Data Specification (MDS), “a digital tool that helps cities to better manage transportation in the public right of way. MDS standardises communication and data-sharing between cities and private (micro)mobility providers, such as e-scooter and bike share companies. This allows cities to share and validate policy digitally, enabling vehicle management and better outcomes for residents. Plus, it provides mobility service providers with a framework they can re-use in new markets, allowing for seamless collaboration that saves time and money”. The MDS has gained a lot of attention from cities and the micromobility industry since it was introduced by the LA Department of Transport (US) in September 2018. It builds on the GBFS standard (General Bikeshare Feed Specification) by expanding on what additional data cities could require from mobility operators. Unlike the GBFS, in addition to the status of available vehicles the MDS also specifies how information should be shared about vehicles that are unavailable due to redistribution, maintenance, or low battery through vehicle event status changes. The MDS has also introduced the concept of sharing data for trips, including starts, ends, and entire “breadcrumb” trip trajectories. While the MDS was initially designed for dockless bikes and scooters, and currently only specifies how data from these services should be shared, many cities hope to expand these data sharing standards to other services, such as ridesharing. The MDS is not without controversy: concerns have been early raised by major players in the market, such as Uber, which have sued LADOT over what the company considers too stringent data-sharing requirements. This is only one reason why the MDS is being examined by some EU countries to assess compliance with the GDPR, where the TOMP working group is working on the alternative City Data Standard for Mobility (CDS-M) API. The TOMP-WG (Transport Operator, MaaS Provider – Working Group) is “a collaborative initiative to create a standardized language for the technical communication between Transport Operators and MaaS Providers within the MaaS ecosystem by means of an API”.

- A compromise solution is that where all parties trust a 3rd party that handles all data. Such party can be an academic institution, a non-profit, or a data analysis platform, such as Fluctuo, Vianova, Populus, or Remix, to name a few. This is usually a cost- and time-effective option for cities that do not have the required data science expertise, but could eventually lead to some sort of vendor lock-in. The much talked-about recent acquisition of Remix by Via (a DRT service provider) for $100 million is only one example how valuable data is for transportation planning, where mobility operators (such as Via) can leverage such data to provide evidence to cities on the convenience of incorporating their services. Also remarkably, Factual has joined forces with CARNET and several other stakeholders under the MultiDEPART project, funded by the EIT Urban Mobility, to develop a dashboard and tools for cities to plan, manage, and monitor vendor-agnostic DRT solutions.

So, of the three above described approaches to mobility data sharing, the decision which one to pursue ultimately basically comes down to how much risk, and how much active intervention, in terms of data processing and analysis, cities are willing, or are prepared to take. The price tag (to be) associated to mobility data remains one of the most complex issues to address.

Figure 2 Pros and cons of the three approaches to mobility data sharing (source: own elaboration based on the International Transport Forum and Populus)

Data makes MaaS happen

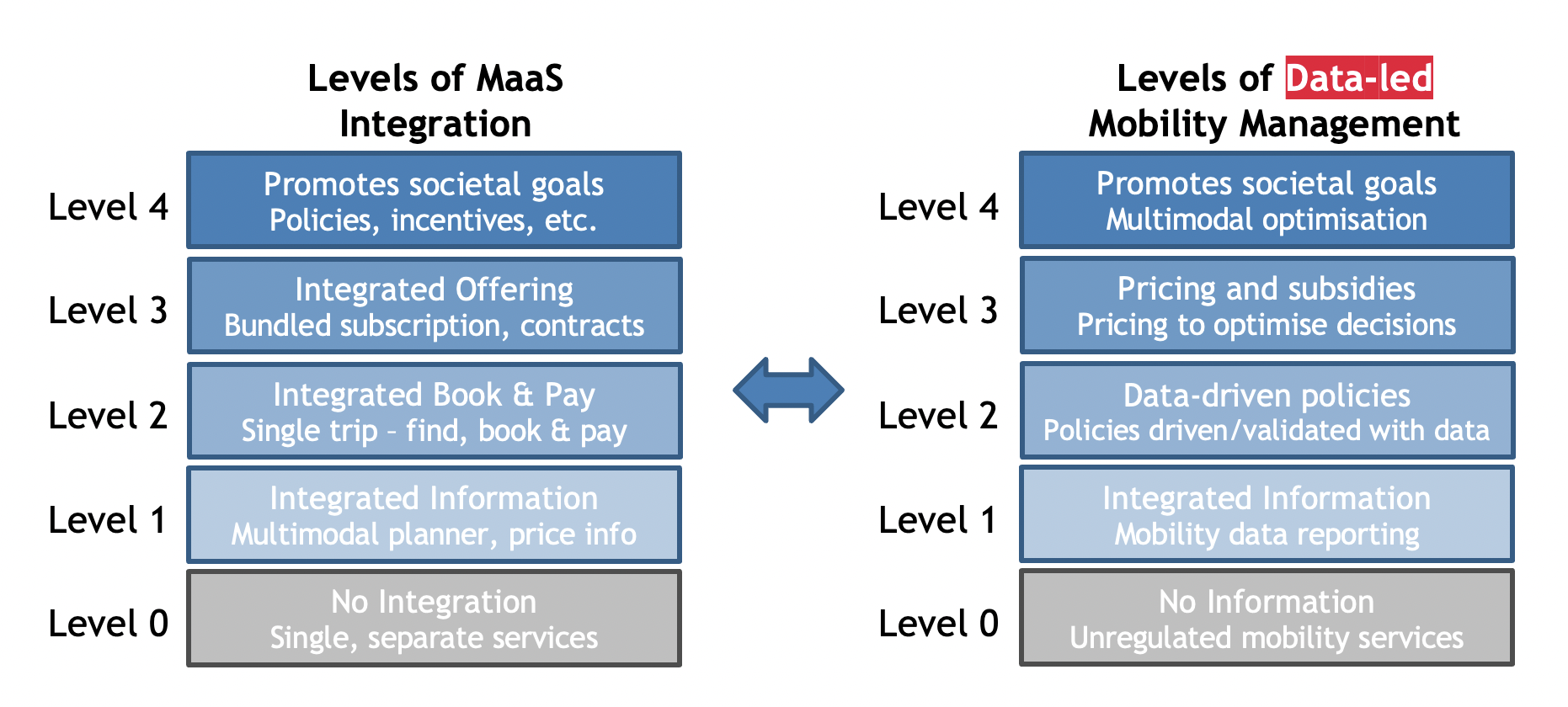

Data is of utmost importance to sustain effective MaaS that maximises public benefit and increases public transport ridership while establishing a level playing field for privately held mobility services to thrive. Analogous to the widely referenced four levels of MaaS integration topology, four levels of Mobility Management are presented, highlighting the key contribution of mobility data in each level.

Figure 3 Levels of MaaS Integration linked to Levels of Data-led mobility management (source: Populus)

- In recent years, many cities have implemented different sorts of Level 1 data-led mobility management by mandating access to mobility datasets from private mobility operators, basically to oversee their operation in the public right of way. Typically, data is required as a pre-requisite to be granted a license to operate, and such information is basically used to monitor very elementary adherence to city ordinances. SMOU is a remarkable example how a city-led mobility app has incorporated all the information on the available offer of bike-, moped-, and car-sharing in the city of Barcelona.

- Level 2 is achieved when cities are able to leverage the data they receive from mobility operators to make more informed decisions and set more effective mobility policies, contributing to alleviating transport externalities, such as congestion and climate impacts, and addressing equity goals. Examples of data-driven policies that might be implemented by cities to manage mobility fleets include:

/ Parking: definition of geospatial areas (geofencing) for preferred and/or restricted parking to protect pedestrian safety or other needs

/ Trips: definition of routes, or lanes, where micromobility or other types of vehicles have priority over other road users

/ Equity: cities might require or subsidise (see Level 3) fleet services in an area that is underserved by other means of transport, or where specific micro-incentives are put in place where, for instance, first/last mile trips using micromobility services are subsidised if and only these trips connect users to public transport hubs (here, continuity of data under a MaaS scheme is needed, so that the policy maker can verify that incentivised trips actually feed public transport, for instance)

/ Fleet size: cities might want to set a minimum level of service or maximum fleet size per each allowed service area

Given that most traveller decisions are largely influenced by time and cost, pricing is an incredibly important tool for public agencies to leverage to shape desired transportation outcomes.

- Level 3 mobility management is achieved when cities effectively leverage pricing strategies, including subsidies, to influence how travellers decide whether to walk, drive, use public transport, shared mobility services, or hail a ride. Many cities overseeing shared micromobility programs have begun to implement more complex policies for pricing the public right-of-way, including parking fees (applied to restricted parking areas), fines for non-compliance with equity policies, and fees for riding in unauthorised zones. While setting a fair price for access to roads, kerbs, and on/off-street parking is an important mechanism for cities to influence traveller behaviour, also important are subsidies. Public transportation services are typically heavily subsidised because they are viewed as providing a significant public utility – in short, public transport enables cities to move more people more efficiently than would otherwise be possible if they all drove individual vehicles. Similarly, as new private mobility services continue to expand, it is important for cities to determine when and where private mobility services provide social benefit to consider subsidising them. It goes without saying that public subsidies must be implemented in the most transparent, cost-efficient, targeted way, and be designed to address Key Performance Indicators included in cities’ mobility plans.

Related to the above, Rideal is a versatile SaaS platform that we at Factual have developed that can be plugged in to any existing MaaS or mobility operator backend platform and be used to design and manage micro-incentives programmes to nudge behavioural change towards more sustainable mobility and monitor its effectiveness in real-time.

Subsidising shared mobility with public money is not new. For example, prior to the emergence of venture-backed electric scooter companies, the majority of bikeshare systems received public subsidies. Moreover, important industry stakeholders, such as the UITP, or POLIS, to name some, are embracing the idea of micro-incentives to any mobility service available in a city as a way to implement more efficient mobility strategies, where availability of data provided by / shared through MaaS platforms is critical.

Key examples of when cities may wish to provide incentives to private mobility operators include:

- Supporting first/last-mile access to mass transit, for instance by incentivising micromobility services

- Expanding transportation access in underserved areas, for instance by incentivising ride-hailing or DRT

- Shifting travellers to certain modes, and in certain time frames, to reduce congestion during peak transit times, flattening demand curves

- Supporting (incentivising) mobility services that have a lower carbon footprint than personal vehicles

Today, many cities have realised Level 1, 2, and perhaps 3 of mobility management, though micro-incentives are still a nascent idea which we at Factual are proposing with our Rideal.

Third party mobility data analytics platforms deliver Levels 1 to 3 mobility management solutions for cities to manage multiple shared mobility services, including shared bikes, scooters, mopeds, and cars, but few cities have implemented mobility management beyond micromobility, and cities are struggling to effectively implement mobility management policies to optimise across the multiple transportation modes, other than micromobility.

- With Level 4 mobility management, public agencies will be able to influence how travellers make transportation decisions across modes to promote societal goals: reducing transportation climate impacts, alleviating congestion, and expanding equitable access to mobility. To reach Level 4 mobility management, cities will need access to data from the various transportation services delivered on their public right-of-way to make data driven decisions, including the implementation of pricing and incentives. Level 4 mobility management can more easily be achieved alongside Level 4 MaaS solutions. That is, the mechanism through which real-time information about transportation options, and specifically new pricing and subsidies, could be more easily delivered to a large population of travellers through one, or more likely, multiple, MaaS consumer-facing applications.

After all, mobility data sharing will not just happen overnight. A forward-looking level playing field that does not undermine innovation and competitiveness from new mobility operators must be used as a lever for it to happen. The price tag to be put on mobility data remains an unknown, where the value of such data is an even more abstract related concept. And one that is much more interesting.

Factual is an innovation and strategy firm committed to transforming mobility. Follow us or get in touch!