Author: Josep Laborda

It’s the end of the world as we know It (and we at Factual feel fine!)

Nothing is more fitting today than this old R.E.M. song of the eighties, arguably the official anthem of 2020, the year when the corona crisis turned our lives upside down, disrupted businesses and global economies in unprecedented ways, and forced the world to a great reset. The disruption to everyday life has, however, unleashed an interesting and positive side effect: in major urban areas across the world pollution levels have dropped to historically low levels, revealing incredibly blue skies, and a more than evident cause-and-effect link to drastically reduced mobility imposed by lockdowns. Moreover, it all has produced a fundamental change of mindset on people and organisations that will linger on: are we ever back to commuting to work as we used to, or will telecommuting stay? Is increased environmental awareness a fad or a permanent trend? How can public transport emerge stronger after plummeted ridership during the pandemic? Will Mobility as a Service finally thrive, and in which flavours? With the entire mobility industry realigning to a new era, we now have the unique opportunity of rethinking mobility and build back better as we try to respond to the challenges posed by a continuously changing environment, a “now normal” in Seth Godin’s terms. So we hit on our 9+1 key trends in urban mobility revolving around technology, societal, political, regulatory, and environmental aspects. Our list does not aim to be comprehensive (neither in terms of the themes, nor of the geography covered) nor do we intend to provide closed answers; rather, our goal is to identify some relevant trends and kick-start the discussion. And in doing this, we highlight the key underlying economic factors pervading every trend, including new business models unfolding, mergers and acquisitions, etc. So show me the money!

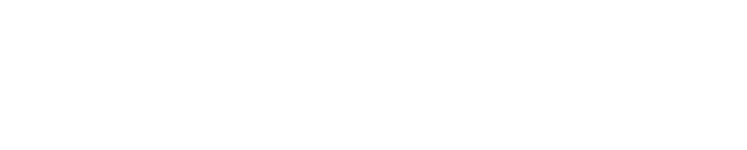

1/ The big picture: a strong but uneven recovery, with big structural changes taking shape

Mobility will rebound strongly in 2021, following the expected recovery of the global economy. This assumes that the COVID-19 vaccine is delivered with no major surprises. The recovery will be strong in emerging countries, where pre-COVID-19 levels will be surpassed already in 2021; but it will be weaker in developed countries, especially in Europe and Japan, where stability will probably not be reached until 2022/23. Preparing for what The Economist calls the 90% Economy will be especially relevant in the mobility industry that will be impacted significantly by some trends –like telecommuting- that the pandemic has accelerated and will not be reversed (see below). Mode-wise, the recovery will be faster for individual modes (like private car, motorcycles, and mopeds) and much slower for collective modes of transport, especially public transport, that in spite of emerging as a winner of the COVID-19 crisis, especially in Europe, will need to cope –at least temporarily- with the challenge to guarantee physical distancing.

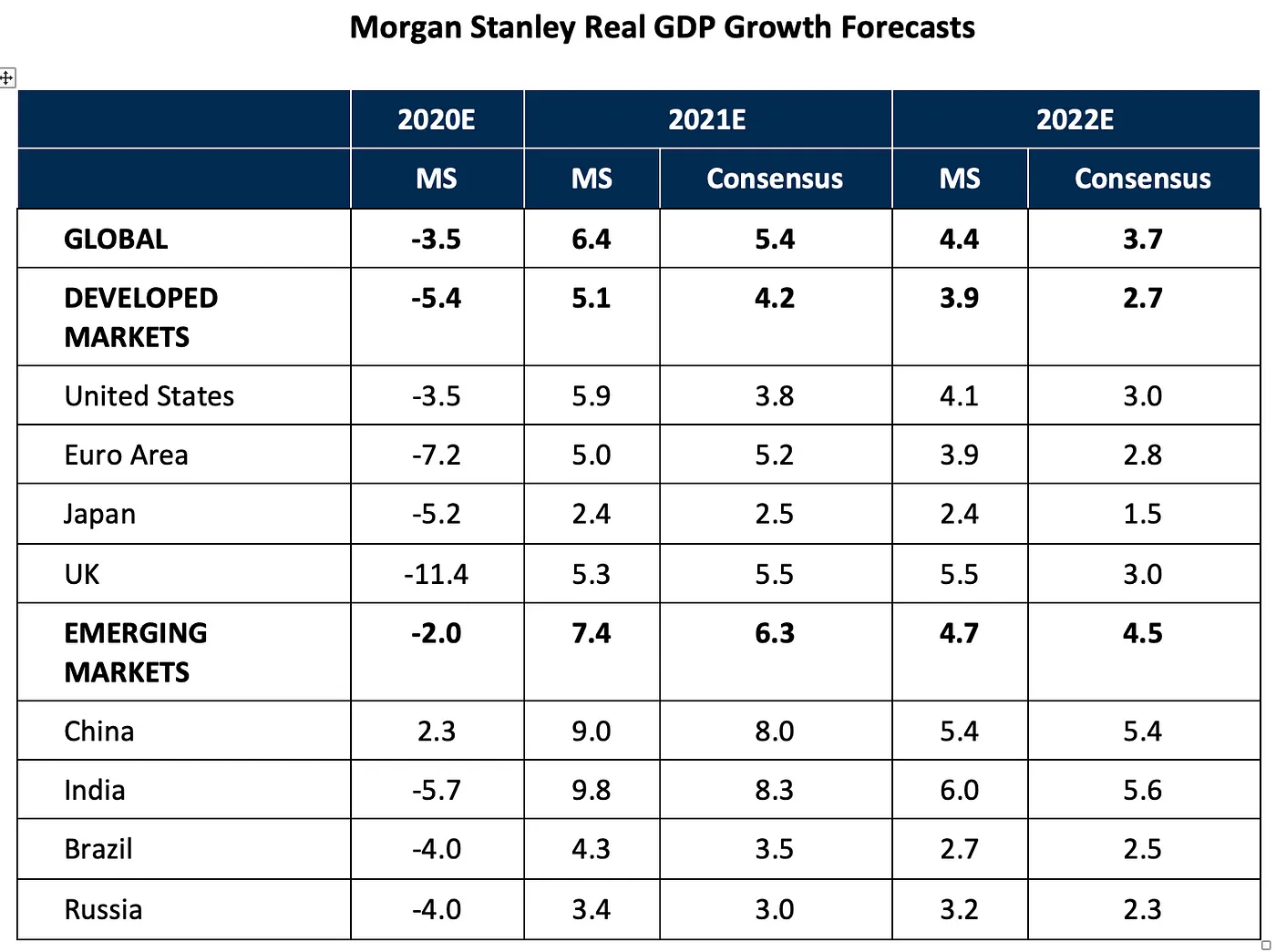

2/ There is a positive side of COVID-19 on mobility… and it is here to stay!

It’s not fake news: some of the pandemic context changes are good and for good. The boost of environmental awareness will remain, and it will be a cornerstone for implementing more sustainable mobility policies. The so-called tactical urbanism is an example: pop-up bike lanes, parking spaces removed, and other pilot tests deployed in many cities to limit motorized traffic will become permanent aiming to improve air quality and develop more liveable cities for pedestrians and cyclists. Another key aspect is the rise of telecommuting, which will go from being residual to impacting up to around 1/3 of employees, especially in metropolitan areas. We have estimated that in the case of the Barcelona region, this can translate into a reduction of commuting trips of around 10–12% and, most importantly, it can flatten significantly the rush hour traffic curve and, with it, the level of congestion. However, will the reduction of road traffic due to telecommuting be compensated -totally or in part- by the rise of e-commerce?

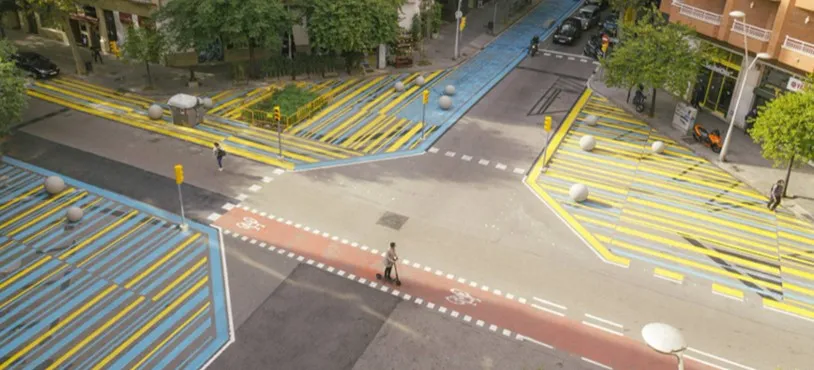

3/ Public transport can be paradoxically one of the winners of the COVID-19 crisis… but it will need to change drastically

Public transport has been severely hit by the COVID-19: ridership plummeted initially, then recovered quite quickly but stalled with the second wave. Looking ahead, it will take time to recover the pre-COVID-19 occupancy levels. Not surprisingly, its finances will suffer: the UITP projects 40 billion € hit for European public transport only in 2020. Paradoxically, however, public transport is likely to emerge stronger from the COVID-19, especially in Europe, as there is strong political agreement that it should remain the backbone of mobility in our cities if we want to reach our environmental and social equity goals. In a context of growing government budgetary constraints, public transport will have to seek increased efficiency in low demand areas through two main levers: i) increased importance of Demand Responsive Transport (DRT) services as a way to improve average load factors and accessibility, while controlling physical distancing if necessary; ii) concentrating the scarce resources on the core network and cooperate with third parties to facilitate the first/last mile.

4/ Progressive convergence between public and private modes of transport

The pursuit of increased efficiency in public transport will progressively open the door to a much more targeted management of public subsidies. This move towards more targeted subsidies (we like to call them microsubsidies) will imply, in practice, a move from subsidising certain modes of transport (very often linked to public operators) to subsidising people. Microsubsidies will allow targeting individual users, taking into account their personal circumstances (age, income, etc) and those of their journey (time, mode of transport, type of vehicle, level of occupancy, etc) and do so in real time. This will have important implications: subsidies will become more equitable, as they will only target those individuals that need them (thus generating important savings); and they will become more efficient, as it will be possible to design them in a way that they incentivise certain desired behaviours (linked to sustainability or reduced congestion, for example). And ultimately, microsubsidies will facilitate a progressive integration between public and private modes of transport through MaaS platforms.

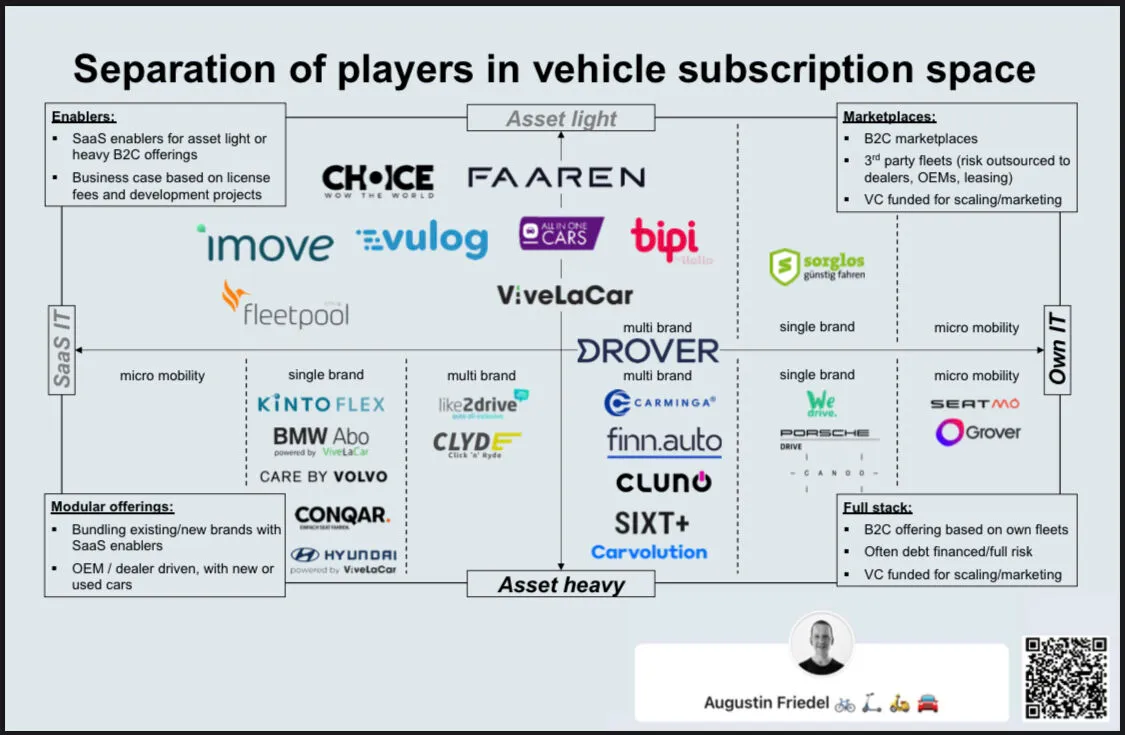

5/ EVs at the tipping point and car subscription market on the rise

EVs have increased their share significantly in 2020 (from 3% to around 10% in the EU in just one year) and this will continue in 2021 thanks to various interconnected factors: fuel efficiency targets (CO2 reduction) imposed by the EU, closing in on TCO parity between EVs and ICE vehicles, battery range improvements, charging infrastructure commitments, and increased government subsidies. Even though consumer purchase intent of EVs is increasing, long term confidence remains an issue, so expect car subscription models to expand significantly as a means to lower the entry barrier to EVs, allowing the new technology to be tested without long-term commitment. This will be reinforced by the overall trend to subscribe to a service rather than purchasing a product. In countries most severely hit by the economic crisis derived from COVID-19, there is a risk, however, that consumers choose to buy –less costly- second-hand ICE cars, thus delaying the environmental benefit of a quick adoption of EVs.

6/ The debate on the taxation of road mobility will heat up

Inevitably, as EVs increase their market share (see point 5), there will be a reduction of the tax revenue from fossil fuels (gasoline and diesel, especially) which represent a very important source of funding for governments, especially in Europe. According to ACEA, taxes from fuels and lubricants represented more than 50% of the 440 billion euros of fiscal income from motor vehicles collected in main European countries in 2019 (see chart below). With public finances undergoing a very delicate situation due to COVID-19, the debate on how to best tax road mobility and make up for the lost resources will move upwards in the social and political agenda, both at a national and at an EU level. Expect the following three options to be further explored: i) in countries (like Spain) where fuel taxation is comparatively low there will be pressure to bring it closer to the EU average; ii) some sort of CO2 tax or Emission Trading System covering the transport sector; and iii) financing infrastructure through pay per use schemes.

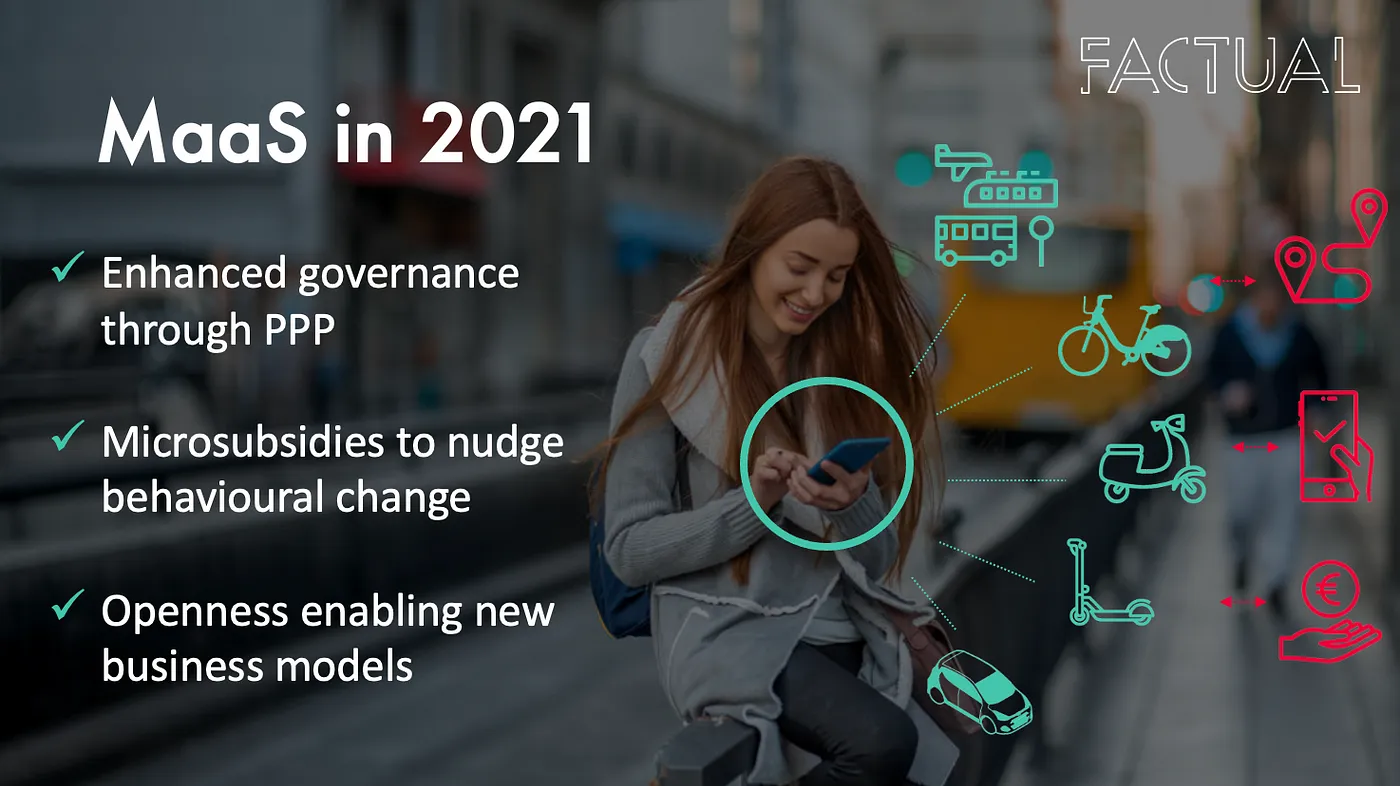

7/ Mobility as a Service (MaaS) will continue maturing, but do not expect it to boom, just not yet

So much ado has been made on MaaS in recent years, with analysts that keep forecasting a market opportunity worth hundreds of billions of € up to 2027. Thought leaders in the mobility space have in 2020 engaged into a very active exchange of insights, particularly on the challenges for realising MaaS as a viable business model (if you haven’t, yet, read the post by David Zipper that triggered the discussion, and the timely replies by Boyd Cohen, Sampo Hietanen, or Aurelien Cottet, among others).

We highlight some of the key factors for MaaS to thrive: economies of scale must be unlocked, driven by massive user adoption, and this is highly dependent on generating trust among the different players in the mobility ecosystem, public and private; governance (not technology) will remain the actual cornerstone of MaaS, where the optimal balance between public leadership enabling social good, and enabling a level playing field for private Mobility Service Providers (MSP) to render profitable results should be ensured; B2C MaaS has proven to be extremely challenging, and so we rather see more room for growth in corporate MaaS for business travel and employee mobility to the workplace; nudging change (meaning adoption of MaaS) in mobility behaviour will be a matter of addressing user needs in a much more tailored way, “one size fits all” is more than ever the wrong approach (this is also very pertinent for public transport!) and those MaaS providers that understand this, for example by integrating highly targeted incentives or microsubsidies schemes, will gain competitive advantage.

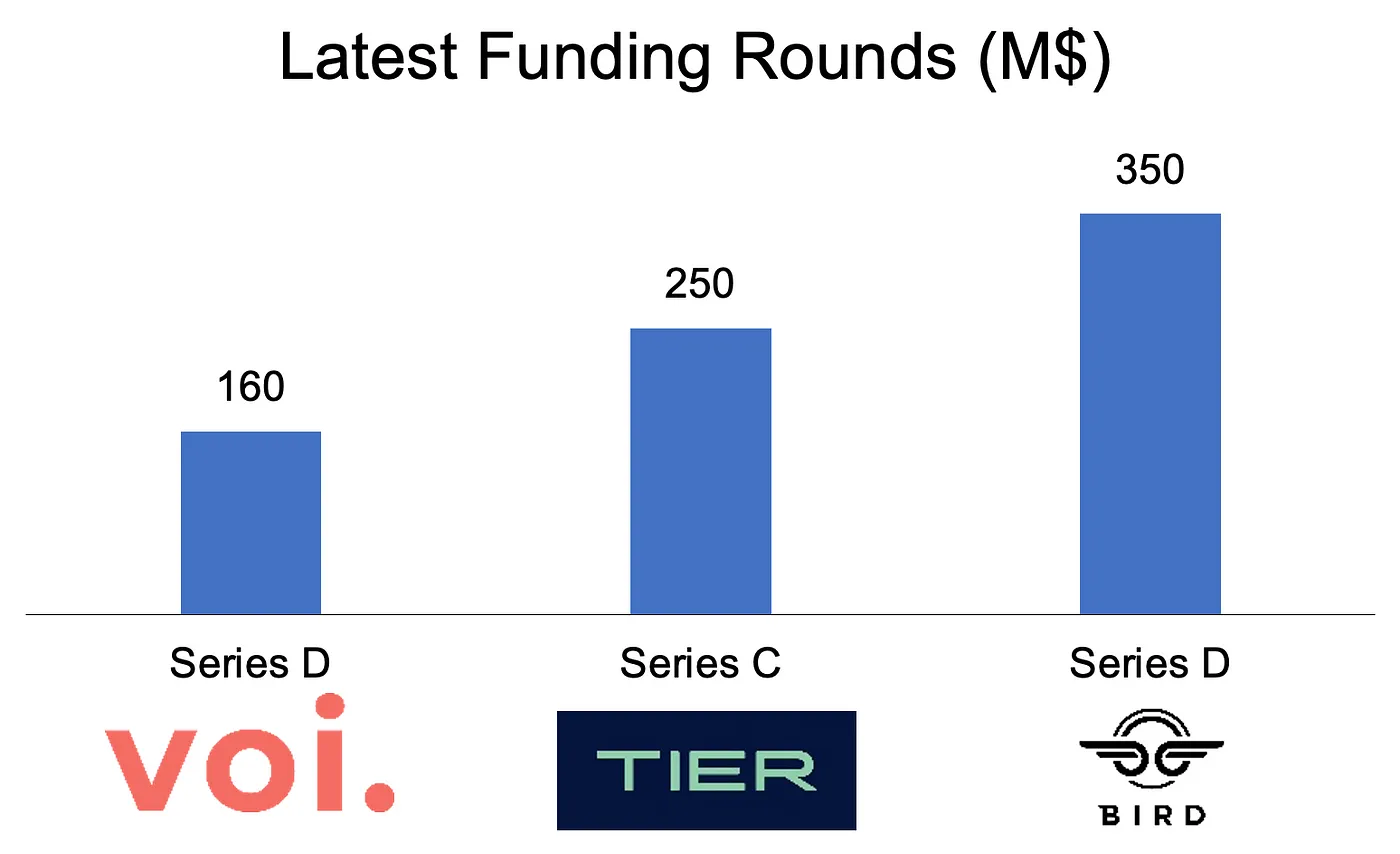

8/ Micromobility: concentration vs competition… Who will win?

After some initial unprofitable experiences (such as with Ofo or Mobike, which recently halted operations), micromobility operators need to become profitable companies. Most of the services that bloomed overnight and landed in many cities worldwide three years ago, some of them with just a bunch of e-scooters (<100) and very low city coverage, struggled with profitability. The pandemic has increased these sufferings, as ridership has fallen with the lockdowns and companies have had to adjust. But in a post-COVID-19 scenario, micromobility appears as one of the winning modes, as users care increasingly about physical distancing and sustainability. The processes of mergers and acquisitions (e.g. Tier, Lime or Bird) and even vertical integrations (e.g. Superpedestrian) that started last year have been accelerated by the pandemic and will continue in the coming months, aiming to ensure their economic sustainability. Overall investment, however, is not expected to reach the astonishing levels reached in 2018 and 2019. Increased concentration will likely raise competition policy concerns among local authorities. But with a limited share in the total number of journeys and with close substitutes (like privately owned e-scooters and e-bikes, walking or public transport) these concerns are likely to be overcome.

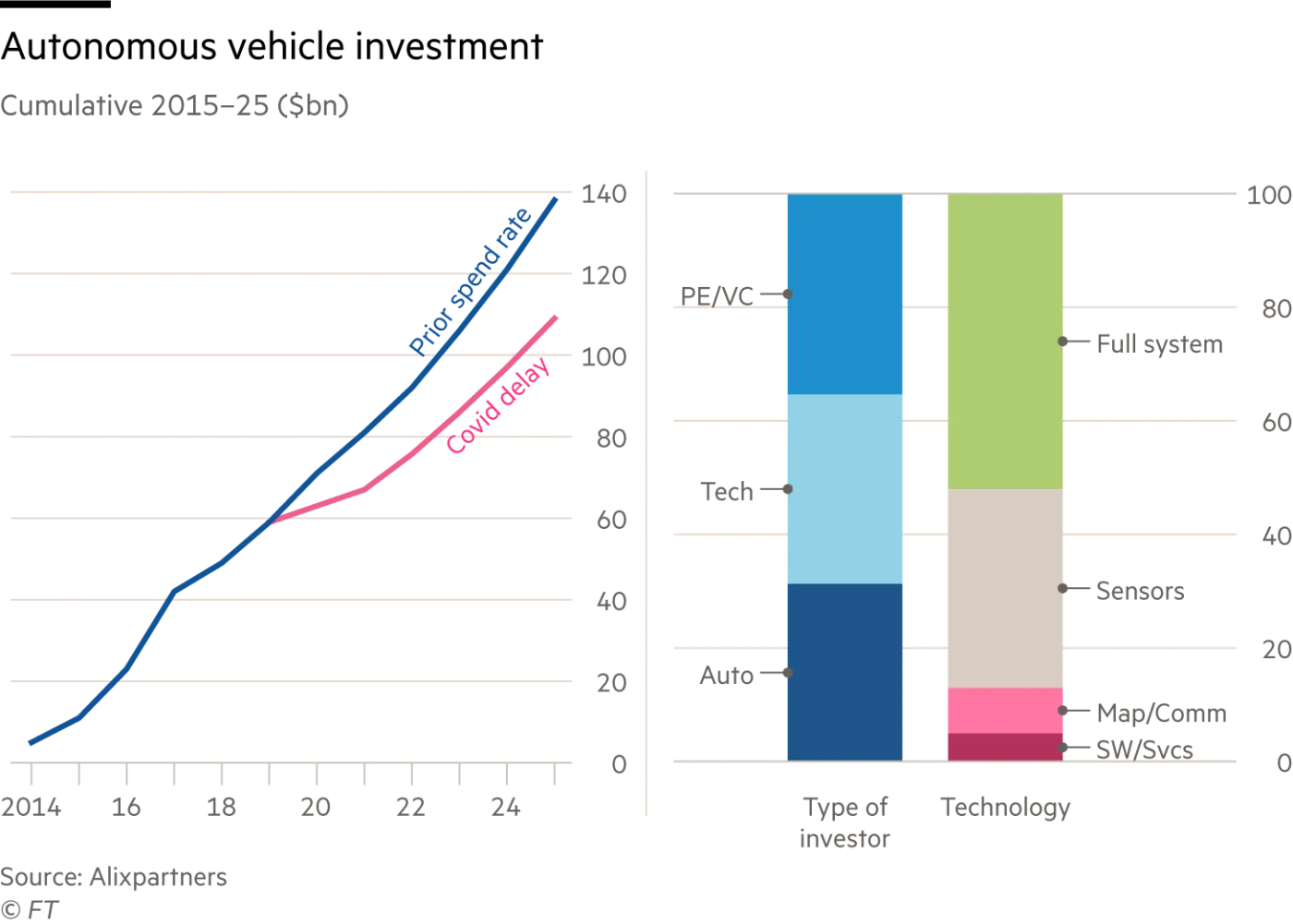

9/ AVs will continue their path towards generalized deployment… more surely than slowly

For sure, AVs will not reach their tipping point in 2021, but they will continue their unstoppable drive towards generalised deployment. After some years where there has probably been more hype than realism, today both experts and industry insiders prefer to be cautious, but this need not be confused with a fundamental reassessment of expectations. Actually, this cycle is typical of disruptive technologies. The huge amounts of investment that the industry keeps attracting is probably the most reassuring indicator that the tipping point will be reached sooner than later, as John Krafcik (Waymo’s CEO) predicts. In 2021 we will probably see a shift in focus from technology towards implementation of fully autonomous commercial services, such as ride-hailing offered by Waymo in Phoenix (US) and Alibaba-backed AutoX in Shenzhen (China), or the parcel delivery service from Nuro in California. The race to expand beyond specific operational areas will require big pockets, so expect Alphabet (Waymo), Amazon (Zoox), Tesla or Apple to double their bet and challenge traditional automotive OEMs. On the regulation side, there will be a push towards increased convergence/harmonisation of regulatory frameworks in key regions (US, Europe, China), a difficult but probably unavoidable process. The readiness of road infrastructure will be key in the transition towards pervasiveness of AVs.

9+1: now it’s your turn!

We leave it here, for the moment. So now you can love it, like it, hate it, share it, but most importantly discuss it! We’re eager to know your predictions. What does your crystal ball tell?

/ Bonus track: It’s The End Of The World As We Know It (And I Feel Fine) — R.E.M. /